New York City’s parks are more vital than ever—but their future funding is uncertain. The city faces an $8 to $10 billion budget gap in the years ahead, compounded by the potential loss of billions in federal dollars. Leaders will soon have to make some tough decisions, and in the past, parks have suffered: last year, the Department of Parks & Recreation (NYC Parks) absorbed a $20 million cut and met less than one-third of its $725 million in state-of-good repair needs amid record-high usage. To address this challenge, policymakers will need to pursue new ideas to generate revenue that can help meet these growing needs.

One achievable option is a thoughtful expansion of concessions in parks and open spaces, with a goal of opening 20 new restaurants and destination-worthy concessions by 2030, alongside a pilot to create low-cost concessions in shipping containers, with the revenue directed to parks’ maintenance needs. This effort could generate $10 million or more in recurring operating dollars, enough to hire 100 skilled gardeners, foresters, rangers, and other full-time maintenance staff.

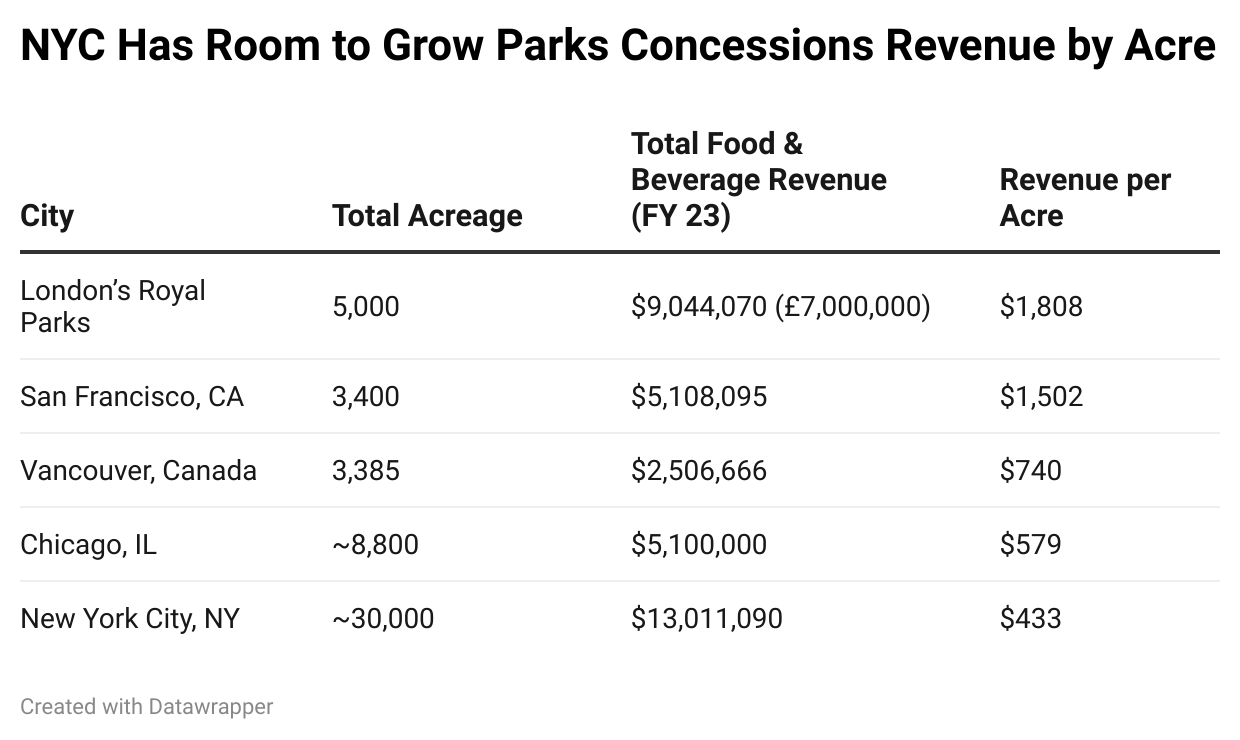

Although the city has long permitted concessions in public parks, there are surprisingly few restaurants, cafes, and new visitor-attracting concessions in parks across the five boroughs. Across the more than 30,000 acres of parkland in the five boroughs, the city licenses just 15 spaces to restaurants—two of which are open only for private events, and three of which are located on golf courses and marinas—and seven to cafes.1 More than 50 percent of existing parks concessions are mobile carts or food trucks, and the city has added few new recreational concessions in recent years.2 Where these concessions do exist, they invariably enhance the experience of parkgoers. New York City has made some modest progress in recent years, including the opening of vibrant venues like McCarren Parkhouse and the Queensboro Oval and new efforts to add concessions from West 4th Street to Orchard Beach. However, this report finds that New York lags several other cities in adding new concessions that make parks more appealing while simultaneously boosting revenues that parks can use to fund critical operations and maintenance. For example, in recent years, Minneapolis added James Beard Award–winning restaurant Owámni to its waterfront park, Chicago has opened beachside bars, eateries and recreational rentals along its lakefront, and Philadelphia has had great success with its mobile beer garden, Parks on Tap.

To be clear, parks are a public good that should be sufficiently funded through city tax levy dollars and not expected to pay for themselves. But faced with decades of inadequate funding and a darkening financial outlook, policymakers will need to think creatively about ways to achieve sustained funding increases—including new opportunities to generate revenue in parks.

New York has also added new parks concessions in recent years. Brooklyn Bridge Park alone has 11 restaurants, cafes, and ice cream shops. But the lion’s share of the restaurants, cafes, and other destination-worthy concessions are in a small handful of parks. Across more than 1,700 parks, there are numerous untapped opportunities to add a thoughtful new concession or two.

This report urges city officials to embrace a modest expansion of concessions in parks across the five boroughs—and take steps to ensure all revenues from these new concessions stays in parks. We recommend that City Hall launch a new effort to create 20 destination concessions in parks across the city, with the goal of improving the visitor experience while generating an additional $10 million in annual revenue. To ensure that parks hold onto new revenue, city leaders should distribute concessions revenue through one or more designated “trusted partners,” with the dollars directed toward parks maintenance needs citywide, or amending the City Charter to enable Parks to capture a portion of its revenues. A new Concessions Investment Fund—launched in partnership with New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC)—could attract private capital to revitalize underused park properties, and NYC Parks could test flexible concession models to lower costs and expand access. And City Hall should spearhead an effort to standardize concessions revenue-sharing agreements across agencies and their nonprofit partners.

Between 2010 and 2022, our research found that the money brought in by parks concessions—the agency’s largest source of revenue—flatlined around $40 million, declining 25 percent since 2012 after adjusting for inflation.3 There has been a notable spike in recent years, largely from the renegotiation of agreements for existing concessions in FY23 and the introduction of new surcharges on golf courses and other facilities. NYC Parks notched $52 million in concessions revenue in 2023, with food and beverage making up about a third of that total. However, concessions revenue is still 9.5 percent lower today than it was 15 years ago after adjusting for inflation.4

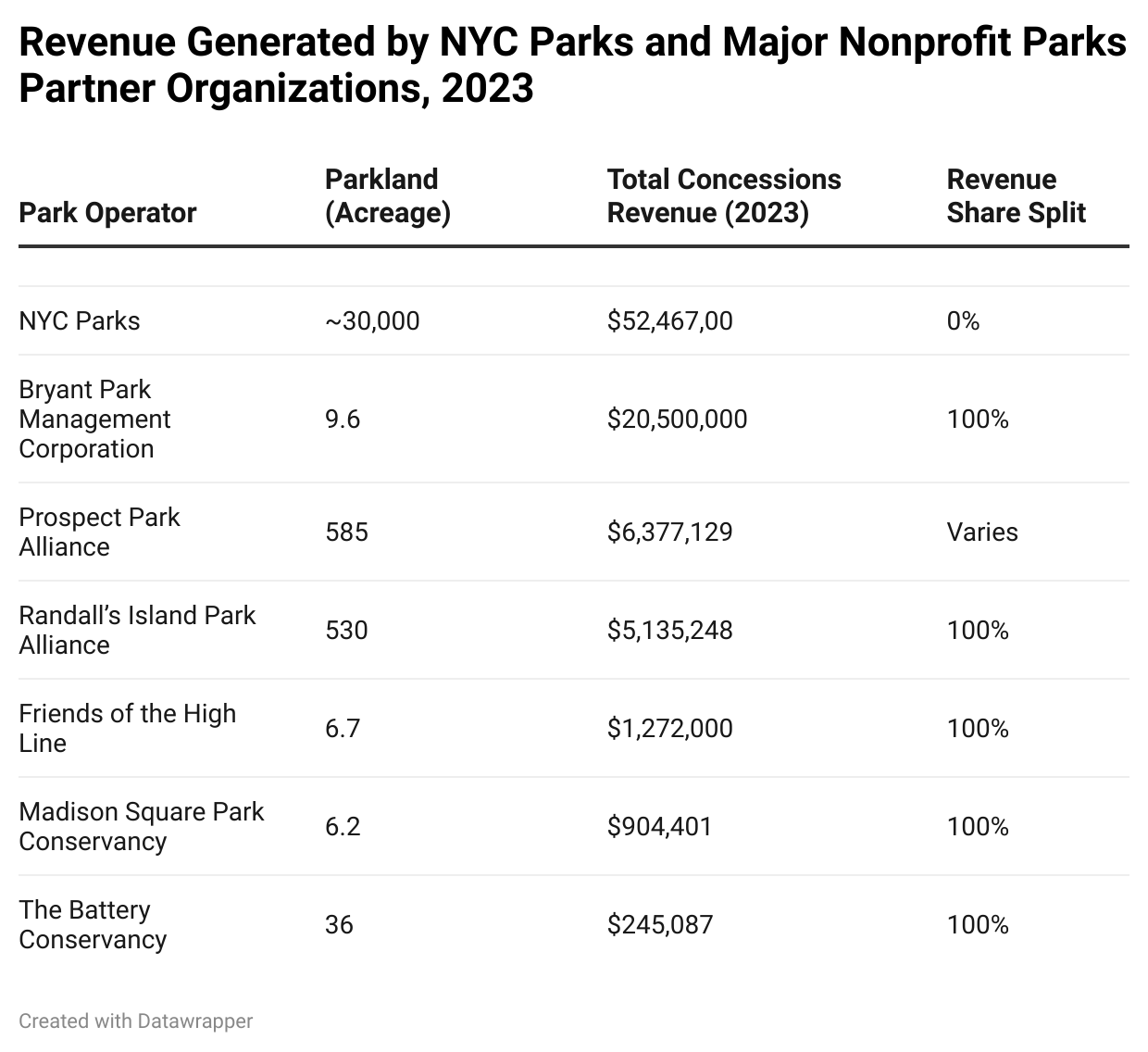

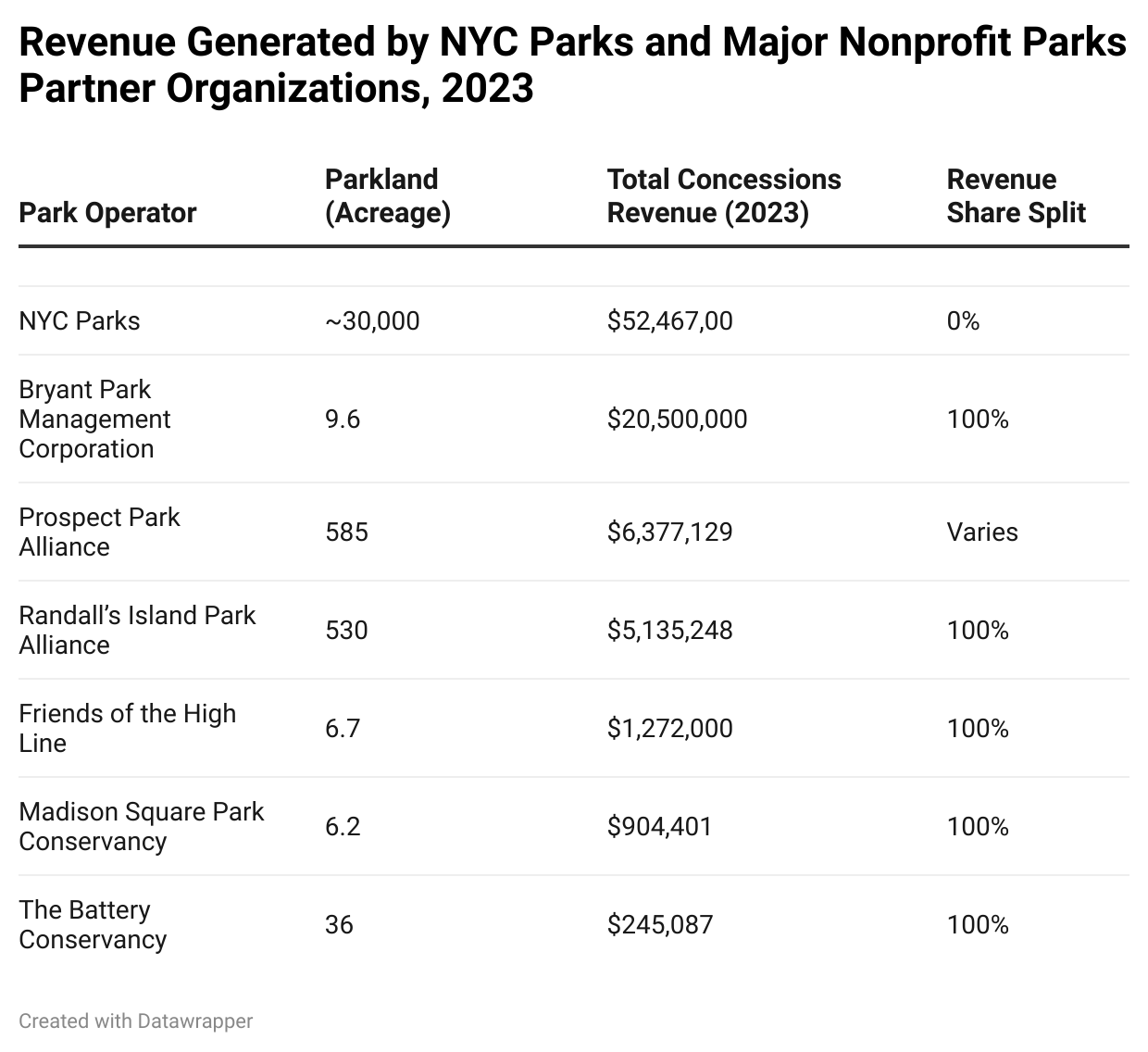

One fundamental disincentive to boost concessions revenue further is that none of the revenue from concessions agreements with the agency flows back into the city’s public parks. Instead, all revenue returns to the city’s General Fund, which is then allocated through the city’s annual budget process. But that isn’t the case for all the city’s parks: a small number of parks supported by nonprofit conservancy and alliance groups operate under specific agreements with the city that enable them to capture a portion of revenue—typically most, if not all, of it—to help offset maintenance needs.

“Parks are badly in need of a model to hold onto money locally,” says Christopher Rizzo, an attorney in environmental law at Carter, Ledyard and Milburn, and former chair of the Friends of Van Cortlandt Park (now VCP Alliance). “And that model must ensure that NYC Parks’ existing budget is not diminished based on new revenue that the agency, its conservancies, and other park stewards are able to generally locally.”

Where parks can hold on to concessions revenue, it invariably boosts park quality while improving the experience of parkgoers. Prospect Park hosts popular offshoots of local eateries Winner Bakery and Lark Café, along with coffee shops, tacos, and the weekly Smorgasburg food festival. As the weather warms up, thousands flock to Brooklyn Bridge Park for artisanal pizzas at Fornino. At the High Line, visitors can explore an array of food and beverage vendors at the Chelsea Market Passage. Danny Meyer’s Tacocina is a destination in Domino Park—and his first-ever Shake Shack still draws lines to Madison Square Park. Beyond food and beverages, park goers can relax at a spa on Governors Island or kayak off Hudson River Park.

These dollars make a difference, significantly benefiting maintenance budgets and supporting programs. In total, seven city parks operated by nonprofit partner organizations earned nearly $60 million from concessions in 2023—more than the agency earned in concessions revenue across the entire city. The Prospect Park Alliance generated $6.3 million from concessions-related sales and fees, which covered its field operations and woodlands budget. Although it’s gone global, the original Shake Shack in Madison Square Park still delivers nearly $1 million in annual revenue to the conservancy there—funding a sixth of its operating costs. Other nonprofits have leveraged this model, too: In 2024, the City Parks Foundation earned nearly $500,000 from its food and beverage concession at Central Park’s SummerStage and reinvested those funds directly to pay for free SummerStage programs.

Source: Center for an Urban Future analysis of data from each organization and the New York City FY 2023 Revenue Budget.

Governors Island hosts a diverse range of concessions—everything from bike rentals and oysters to “glamping” and Ethiopian food. Clare Newman, President and CEO of The Trust for Governors Island, a nonprofit organization that holds onto all of its concessions revenue, says the material benefit to the island’s upkeep is substantial. “If you think about it as marginal revenue, even six figure participation can make a difference,” she says. “That can allow us to increase care for the park through additional staffing, maintenance and programming.”

But, Newman stressed, these options just as importantly offer day-trippers plenty to do once their ferry arrives. Concessions make visiting a park even more enjoyable: they boost foot traffic, bolstering public safety; they come with amenities, like restrooms and water fountains (85 city-managed concessions offer public restrooms); and they offer a publicly accessible space, where visitors can treat themselves to a snack or activity. They also create jobs: according to NYC Parks, concessionaires garner an estimated 3,500 positions, not including construction or contractors.

“We view all of our park concessions as partners and amenities to improve the park experience,” says Eric Landau, CEO of Brooklyn Bridge Park, which also holds onto all the concessions revenue it generates to steward the waterfront destination. “The revenue is helpful, but not the sole driver for us.”

Even without the incentive of new revenue for parks, the city’s Parks Department has taken important steps to add concessions in recent years for the benefit of parkgoers, including the highly regarded transformation of the McCarren Parkhouse from an aging locker room into a beautiful and functional new year-round public amenity. NYC Parks is working with the city’s Economic Development Corporation to bring new concessions to Orchard Beach in the Bronx. And the agency is seeking proposals to renovate snack bars at three small parks in Manhattan and to open a café in Greenpoint’s Transmitter Park after years of delays.

But there is still ample untapped opportunity to create concessions in parks. Most community parks and playgrounds close to where New Yorkers live lack any sort of café or kiosk. There are no restaurants, cafes, or other eateries in parks in broad swaths of the city, including south Brooklyn, the L train corridor from Williamsburg to Bushwick, southeastern Queens, and most of the Bronx. Outside of the occasional pushcart, visitors are hard-pressed to find a bottle of water or snack for miles in some of the city’s largest parks, like Flushing Meadows-Corona Park and Pelham Bay Park. In fact, in all of Queens and The Bronx—which, together, are home to almost 4 million people—the NYC Parks website lists six eateries in parks there, three of which are limited to private events.

Many existing structures could become promising concessions sites with some creativity and initial investment. Of the city’s ten field houses in parks, most are open to the public just a few hours per week. Existing bath houses could host rooftop restaurants or year-round steam rooms or saunas. Amphitheaters and bandshells---like the Seuffert Bandshell in Forest Park—could host events with concessions or food trucks. And mobile structures like shipping containers could be designed and deployed to create seasonal concessions opportunities in parks with little or no infrastructure.

This report lays out the challenges hindering parks concessions today, the recent advances made by the city, and the steps needed for a smart, thoughtful expansion of concessions citywide. It also highlights other parks or systems—both within the city, and elsewhere—where concessions revenue is directly applied to parks’ upkeep.

The report concludes that several actions could boost funding from new concessions. First, City Hall could work with NYC Parks to distribute dollars from future concessions through a designated “trusted partner” for enhanced maintenance and programming, capturing a greater portion of revenue for the parks where sites are located and to underserved spaces citywide. Second, a partnership between the New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC) and NYC Parks to launch a Concessions Investment Fund could corral private funds to renovate existing yet underutilized park properties for new usage. With sufficient support, NYC Parks could test out flexible facilities for concessions to lower costs and widen reach. And City Hall could spearhead an effort with OMB, the Law Department, and the Office of the Comptroller to develop a comprehensive, citywide approach to concessions development that streamlines the process, aligns guidance across agencies, and maximizes the benefits for New Yorkers.

Three Key Challenges to Boosting Parks Concessions

The money generated by most parks concessions does not stay with NYC Parks. The City Charter states that “all revenues of the city...from whatsoever source except taxes on real estate, not required by law to not be paid into any other fund or account” goes to what’s known as “the general fund.” The money is collected throughout the year and then allocated to meet agency needs through the budget process. The fund was created to stem corruption and ensure stable financial planning in the wake of the 1970s fiscal crisis, and while its original intent was sound, it has had a chilling effect on parks since: nearly every expert interviewed for this report says that the inability for NYC Parks to capture money generated from concessions in parks discourages the agency from seeking out opportunities to expand or innovate.

Private park operators, like conservancies or alliances, can hold onto concessions revenue through specific agreements with the city. Yet these private partners only manage a fraction of the city’s green spaces, limiting most of the city’s public parks from directly benefiting from new concessions through increased revenues.

The city has an opportunity to expand this model to more parks, potentially by designating an existing trusted nonprofit as the steward of a larger-scale plan to generate more concessions revenue. However, such a plan would likely only first include future revenue, as the city has already budgeted for the use of existing revenue streams.

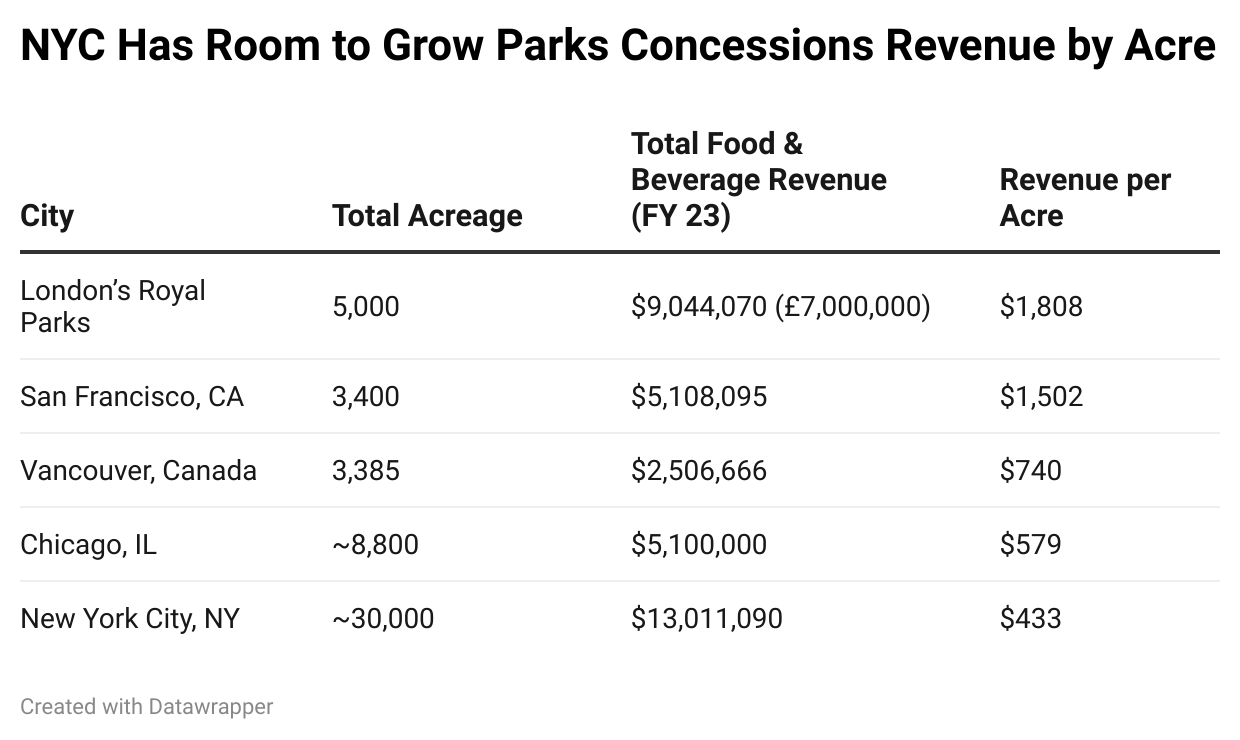

In many cities across the U.S. and globe, respective parks organizations or authorities can both generate concessions revenue and hold onto it.

The Chicago Parks District hires a private company to oversee over 200 park concessions, whose revenue returns to the self-financing authority. That includes Del Campo Tacos on 12th Street Beach and Coup de Main, a massage therapist along Oak Street Beach. Meanwhile, London’s Royal Parks proudly tells patrons that the dollars they spend at thirty locations, like the Serpentine Bar & Kitchen in Hyde Park or St. James’s Park Café, go directly to park maintenance.

In a newly furbished pavilion, Owámni, a Sioux restaurant, was labeled “the best restaurant in the U.S.” when it opened in Minneapolis’s Water Works Park in 2021. That year, it made $1.7 million in revenue. In Minneapolis, concessionaires pay 12 percent of annual gross revenues, rather than monthly rent, to the Parks Board—a preferred approach, according to those we interviewed, due to seasonal changes. Thus, $204,000 of the popular restaurant’s earnings went directly to park maintenance that year. In fact, the agency’s budget in 2023 had to be adjusted up because Owámni “continues to perform at higher levels than expected.”

Source: Center for an Urban Future analysis of budget data from each city’s parks department or concessions operator.

The expectations of park properties are sometimes unrealistic or infeasible. New York City’s parks contain significant untapped opportunities for concessions in buildings—from field houses, pools, and rec centers to storage buildings, historic structures, and pavilions. But to enable more of these spaces to be reactivated for revenue-generating uses, upfront capital investments will need to be made. The gap between what a prospective concessionaire is willing to invest and what the agency can afford to has become an obstacle to more creative concession creation and can lead to lengthy delays and periods of dormancy.

For instance, the agency has made a years-long effort to reactivate the landmarked radio transmitter station inside Greenpoint’s WNYC Transmitter Park, which has hit multiple roadblocks. One of the fundamental challenges has been the lack of capital dollars available to help shore up the dilapidated building before seeking a concessionaire. In response to the previous request for proposals at the site, local entrepreneur Francois Vaxelaire jumped at the change. He saw it as an opportunity to branch out in a setting he knew well: Vaxelaire owns and operates The Lot Radio a few blocks away, an all-in-one radio station, café, and bar. But as the cost of renovation became clear, the business owner soon balked at the price tag.

“We lost a lot of money applying because we had to pay architects and structural engineers who specialized in leaking to come on site and do reports, just for them to say that a huge amount of work had to be done,” says Vaxelaire. “It cost an arm and leg. And at some point, we realized the risk was too big.”

According to experts, this experience is common with city-led parks concessions. The sites often require overhaul and investment that many concessionaires rule out due to cost and risk, while the agency is understandably reluctant to make a major investment in site upgrades with so many other capital needs across the system. Of course, it is reasonable for the city to expect a business to invest capital in a site before opening—but, experts say, the needs often outweigh the willingness of entrepreneurs to commit.

Michael Ayoub, the owner of artisanal pizza pioneer Fornino who previously operated concessions in Brooklyn Botanic Garden and Prospect Park, says the Brooklyn Bridge Park team set up a “white box” space, where utilities, plumbing, and finished interiors were included, for their popular seasonal location near Pier 6. But that wasn’t the case with a recent RFP at Greenpoint’s Monsignor McGolrick Park.

“I ended up not applying. There was barely any seating area, and you had to renovate a bathroom with eight stalls. I can build a kitchen no problem, but I’m not in the toilet paper business,” says Ayoub. “Every building needs some work, but it’s about expectations. It needs to be a symbiotic relationship, not one-sided. You’ll get better concessionaires as a result.”

There are also opportunities to get creative with concessions that parks could be missing out on, due to a lack of funding and support. Clare Newman, of The Trust for Governors Island, says shipping containers have allowed her organization to dramatically expand its offerings to visitors. “Permanent structures in New York City parks and public spaces can cost millions,” says Newman. “But for $100,000, literally, you can outfit a container and get it operable for a small business on a multi-year basis.”

The city’s rules for park concessions stifle potential opportunities. Approvals for a new city-managed parks concession often include several agencies, including the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services, the city’s Office of Management and Budget, and the Franchises and Concessions Review Committee. The review process is stringent by design to ensure that the process maximizes value for the city and its residents and is conducted fairly and transparently. But, according to the experts we interviewed for this report, the terms often make it difficult for concessionaires to operate.

Park organizations described the process as disorienting, where budget officials, city lawyers, and other representatives repeatedly switch positions without rationale, often overstepping the advice of NYC Parks. (Most spoke on background out of fear of retribution.)

First, there is no standardized process for concessions agreements, whether with the agency or through a nonprofit intermediary; what, where, and when they’re allowed to operate—and how revenue is shared—is decided on a case-by-case basis. One park, for example, may be allowed to host four special events a year, while another is permitted ten; one park may be allowed to operate a stall, but a stand nearby is off-limits. Parks are undoubtedly unique in their needs and settings, but experts say the current approach upends timelines and planning.

“Every time we say, ‘Well, we just want to replicate what XYZ conservancy has,’ it’s like, ‘Well, we would never do that deal again. That was a special thing,’” says one park executive. “It’s a ‘choose your own adventure.’ That makes the process hard, and I assume a lot of people do not enter the work, since it’s so uncertain.”

Another hurdle is termination by will. The idea, where NYC Parks can end a parks license at any time if it sees fit, protects the City of New York from liability. It’s legally required under the public trust doctrine, and not a matter where NYC Parks has any discretion. But according to individuals we interviewed, it severely deters concessionaires from applying. “If the city can terminate at will, there can’t be any problems, which is impossible to predict for any business,” says Michael Ayoub, of Fornino. “I’ve done it before, but it’s tough.”

Those we spoke with also repeatedly cited license length as a risky proposition. Current rules limit parks concessions licenses to a maximum of 20 years. But if a concessionaire is expected to put up a substantial amount of money to shore up a property, that timeline doesn’t encourage investment.

“That’s what we got for McCarren Parkhouse, but even longer would be nice, assuming a big chunk of money is required for the build-up,” says Aaron Broudo, a co-founder of BK Bazaar, which raised the capital for, and now manages, Parkhouse. Their latest project, the redevelopment of the Jacob Riis Bathhouse into a hotel, rooftop restaurant and catering hall, received more leeway from the National Parks Service, which manages the land. “It was a 60-year lease, so there are many more people involved,” Broudo added. “It’s much longer and bigger build-out. The time allowed for us to raise the additional dollars required for that.”

Making matters more challenging, there is no playbook for applying to park concessions. When pursuing the bid for WNYC Transmitter Park, Vaxelaire was new to the city’s RFP process. Thankfully, he had help. “I knew someone who had gone through it with the city before,” he says. “They had a template and showed us how to fill it out. But not everyone has that.”

Signs of Progress

The city has made progress, introducing innovative concessions to more parks and open spaces. Perhaps most notable is the opening of Parkhouse in McCarren Park. The previously derelict facility underwent a $3.5 million renovation largely through private funds, using recycled timber and other sustainable features. With glass paneling that opens to the park, the adaptive reuse project now houses a café, WiFi, bar, eatery, ice cream shop, accessible bathroom, and reserved space for North Brooklyn parks maintenance staff and Parks Enforcement Patrol (PEP) officers.

In 2022, NYC Parks and NYCEDC announced a $87 million restoration of the Orchard Beach Pavilion, which looks to revive the 140,000 square-foot facility to its former fame of the “Riviera of the Bronx.” That includes a concessions refresh: the historic stands within the Pavilion will be built out with mechanical, plumbing and electrical services for future tenants. (The first phase is expected to open this summer.)

New Yorkers can also pick up produce at a GrowNYC greenmarket or browse for books at The Strand kiosk in Central Park—both city-run concessions. The agency has expressed interest for potential concessions, or other usages, at Astoria Park Pool and Jackie Robinson Pool, potentially paving the way for all-year activities at pool buildings. Regular performances from Cirque du Soleil are coming to Randall’s Island Park this year, with revenue staying on the island. And the Queensboro Oval, a privately renovated city-run indoor tennis facility underneath the 59th Street Bridge, is one of the most popular park concessions in town.

There are other notable marks of success with the concessions process itself, too. In recent months, NYC Parks has rolled out a “license agreement lite” with reduced requirements and capital commitments to make it easier for private entities to care for parks, which is typically needed if an operator is going to open a concession later. The Department of Hygiene and Mental Health (DOHMH) changed its rules in 2022 to make it easier for parks concessionaires to operate without running water or a bathroom on-site, which makes facilities like newsstands and carts more feasible.

Together, these initiatives offer momentum to activate parks and open spaces with new models that meet the moment of how New Yorkers are using the public realm today. But more can be done to ensure that all parks are benefiting.

Five Recommendations to Boost Funding for Parks Through New Concessions

1. Launch 20 new destination-worthy concessions over the next three years. To realize more of the untapped opportunity to generate concessions revenue in parks, the mayor should launch a major new effort to create 20 destination concessions over the next three years—from new restaurants to year-round spas—that generate maintenance funding while enhancing the experience of parkgoers. A measured expansion of these offerings could help transform underutilized areas of parks into vibrant community hubs and generate as much as $10 million in recurring annual revenue. To jumpstart this effort, the mayor should direct NYC Parks to identify 20 high-potential sites across the five boroughs with community input, prioritize underutilized assets like pool houses and comfort stations for adaptive reuse, and issue RFPs aimed at attracting local entrepreneurs and innovative concessionaires.

2. Designate a trusted partner to capture a greater share of future concessions revenue to reinvest in parks—or amend the City Charter to enable Parks to capture revenue. To ensure that this revenue benefits parks, City Hall should work with NYC Parks to distribute dollars through a trusted nonprofit partner or multiple partners to address the agency’s maintenance and programming needs. The city could also consider creating a new Parks Maintenance Trust or other designated entity that would collect revenue from both new concessions and the renewal of existing license agreements, such as with the stadiums located on parkland. City Hall could also explore an amendment to the City Charter that would enable NYC Parks to hold onto a portion of its revenues over a set target—for instance, all concessions revenue over $50 million. The city could also pilot new efforts to create revenue-sharing agreements with smaller parks organizations including “Friends of” groups.

Importantly, the mayor and City Council should commit to maintaining city tax levy funding at or above a set baseline, so that new revenues are used to benefit parks, not close other budget gaps (this requirement could also be written into the bylaws of a new Parks Maintenance Trust). To ensure that the revenue benefits all parks with unmet maintenance needs, the city should consider an 80-20 revenue split—only for new concessions revenues in parks without existing conservancies—that keeps most of the proceeds in the host park while directing a portion to support green spaces in underserved neighborhoods. Once this system is operational, the City Council could pass legislation requiring NYC Parks to report on how revenue from the Parks Maintenance Trust or similar entity is being allocated.

3. Launch a new Concessions Investment Fund with NYCEDC to renovate and open new concessions in underutilized parks properties. Experts suggest that more than 20 parks properties could provide an opportune setting for a new concession in the future. The pool houses in Astoria Park and Jackie Robinson Park. An abandoned newsstand in Grand Army Plaza. Half-empty maintenance sheds in Sara D. Roosevelt Park and Alley Pond Park. The visitor center in Fort Greene Park. The dilapidated kiosk in Union Square. The bathhouse in Baruch Playground. The Tennis House in Prospect Park. The radio station building in WNYC Transmitter Park. And Worth Square, next to Madison Square Park.

Most of these sites, however, lack the capital investment needed to attract a private sector partner, such as electricity, plumbing, and HVAC—or even a stable structure. Inspired by the renovations of McCarren Parkhouse and the Orchard Beach Pavilion, NYC Parks should launch a new Concessions Investment Fund in partnership with NYCEDC, which could mobilize the upfront capital investment needed to attract private sector investment and help prepare underutilized or empty parks structures to become attractive, revenue-generating concessions.

The agencies could also consider the option of a low-interest revolving loan fund, providing concessionaires with a source of affordable capital and technical assistance focused on the unique needs and opportunities of parks properties. As an added benefit, if some of the capital work is managed directly by NYCEDC, the process is simplified and can often be accomplished much more quickly and affordably than if it flows through the city’s capital process.

4. Pilot a pop-up parks concession program to expand temporary, mobile, and seasonal opportunities citywide. In addition to creating new destination-worthy concessions, the city has a significant opportunity to develop more concessions that fill the gap between brick-and-mortar establishments and mobile pushcarts. To capture new revenues with lower costs of operation and easier deployment than a full RFP for an existing structure, City Hall should work with NYC Parks to pilot a pop-up concession program to reach more parks citywide. The city could also consider launching an RFP for an operator or coordinator of mobile concessions, coordinating with the hundreds of programs taking place in parks across the city to offer audiences options for food and drink while generating revenue for the host park.

There are examples elsewhere to follow. In Philadelphia, the “Parks on Tap” program sees a beer garden travel to a new park each week for 26 weeks straight from April to October, with a portion of sales going back to Philadelphia Parks & Recreation. In Chicago, the 7323 Café operates out of a storage container in Flying Squirrel Park. And locally, the Queens Night Market, although not technically on parkland, brings a destination-worthy event featuring local entrepreneurs to the edges of Flushing Meadows-Corona Park.

5. Reform citywide concessions guidelines to boost high-quality participation in parks concession RFPs. While much can be done to ensure that NYC Parks can both bolster concessions and hold onto a greater share of their revenue, it should be coupled with a concerted effort from City Hall to align processes around concession agreements to attract a stronger pool of bidders. For decades, too many RFPs have seen a limited response or gone unanswered. In addition, differing agreements among agencies can lead to unintentional competition between concessions located on parkland versus Department of Transportation property or other city-owned assets.

To address these obstacles, the mayor should work with all agencies that license concessions to develop a citywide approach to concessions agreement development and revenue-sharing—applying best practices across agencies, simplifying the process wherever possible, and aligning the terms that agencies offer to maximize concessions quality, feasibility, revenue, and benefits for New Yorkers.

Endnotes

1. These restaurants and cafes are located in city parks that are not managed by conservancies or other nonprofit partner organizations.

2. Center for an Urban Future analysis of data from the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services, 2023.

3. John Surico and Eli Dvorkin, Paying for NYC’s Growing Park Needs, Center for an Urban Future, January 2024, https://nycfuture.org/research/paying-for-nycs-growing-parks-needs

4. Center for an Urban Future analysis of data from the NYC Office of Management and Budget’s annual financial plans and from the NYC Council’s annual reports on the preliminary plan for the Department of Parks and Recreation.

_(1)_300_388_bor1_a4a4a4.png)